People you should know: Ibrahim the Mad (1616-1648)

People you should know: Ibrahim the Mad (1616-1648)

The Istanbulletin would like to celebrate some of the people that used to tread these streets. Just like any old city that was the heart of an empire or two, Constantinople has seen its share of heroes and villains, thieves, seers, love torn princesses and batshit crazy despots. Let’s start with one of them. Welcome to the bizarre world of Sultan Ibrahim.

Unlike the short-lived dynasties of Byzantium, the fact that there still are Ottomans eating baguettes in France is due to the harem factor. The primary wives were made because they gave the sultan a son. No marrying some import and hoping for the best. Sultans pumped out sons like a butcher does sausages.

This leaves us with the obvious problem of succession, which the Ottomans got around fairly swiftly. When the sultan died, his most obvious successor would have his brothers killed, or at least locked up.

This leaves us with the obvious problem of succession, which the Ottomans got around fairly swiftly. When the sultan died, his most obvious successor would have his brothers killed, or at least locked up.

Ibrahim was no different. Already marked out as a bit strange, he avoided the bow-string garrote when brothers Osman II and Murad IV ascended to the throne. Instead, they locked him in “The Cage”, a pretty basic cell in the palace. When they died, the empire was left with one choice: to sluice down and enthrone Ibrahim.

And so began a reign that reminds one of the idiotic periods defined by Roman emperors Nero or Elagabalus. Still to this day, some people call the Red Mullet the Sultan Ibrahim, because he used to feed this species of fish with coins rather than food. To say he was unfit to rule is like saying that a Scottish terrier is unfit to saddle and ride.

This suited his mother, Sultan Köşem, who was basically handed the keys to the kingdom. While she drove, Ibrahim sat in the back seat and got up to sticky mischief. He was a DIRTY boy.

Ibrahim dedicated most of his time to doing what most of us would do if we had a harem: getting laid. But, being crazy, just doin’ it with over 250 women was not enough for him. In one account, he would line his concubines up and have them strip naked. Then, in an attempt to be seductive, he would make farmyard noises and gallop between them. Once his blood was up, he would do the deed.

Ibrahim dedicated most of his time to doing what most of us would do if we had a harem: getting laid. But, being crazy, just doin’ it with over 250 women was not enough for him. In one account, he would line his concubines up and have them strip naked. Then, in an attempt to be seductive, he would make farmyard noises and gallop between them. Once his blood was up, he would do the deed.

His tastes for domesticated animals did not stop there. Once, passing by a cow, stopped in his tracks at seeing its hind-quarters and ass. Now, maybe you are thinking, “Come on, Ibrahim. Beastiality? Really?” But, no. Weirder. He had a golden cast made of the cow’s ass and sent it around the empire with the instructions to find a woman whose rear matched it. Even weirder was that they actually found a woman who eventually became his favourite concubine. Her name was Sugar Cube.

She became so powerful that she escaped his most epically crazy decision, which was to have all 280 concubines tied in sacks and drowned in the Bosphorus. This was his barking mad response to a rumour that one of the concubines had been “compromised”.

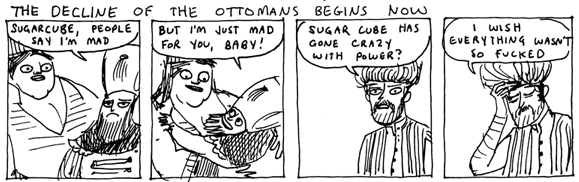

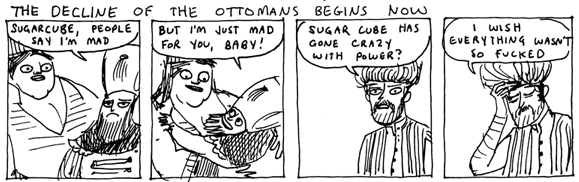

Taken from Hark, a Vagrant by Kate Beaton

Eventually, the chaos that was going on between Ibrahim’s ears came to be reflected in the empire. Public servants went unpaid and things came to a head after Ibrahim raped the daughter of the chief mufti. One rebellion later, Ibrahim was back in his cage, one of his sons installed in his place.

There was never a second sultan called Ibrahim. Because this one was a jerk.